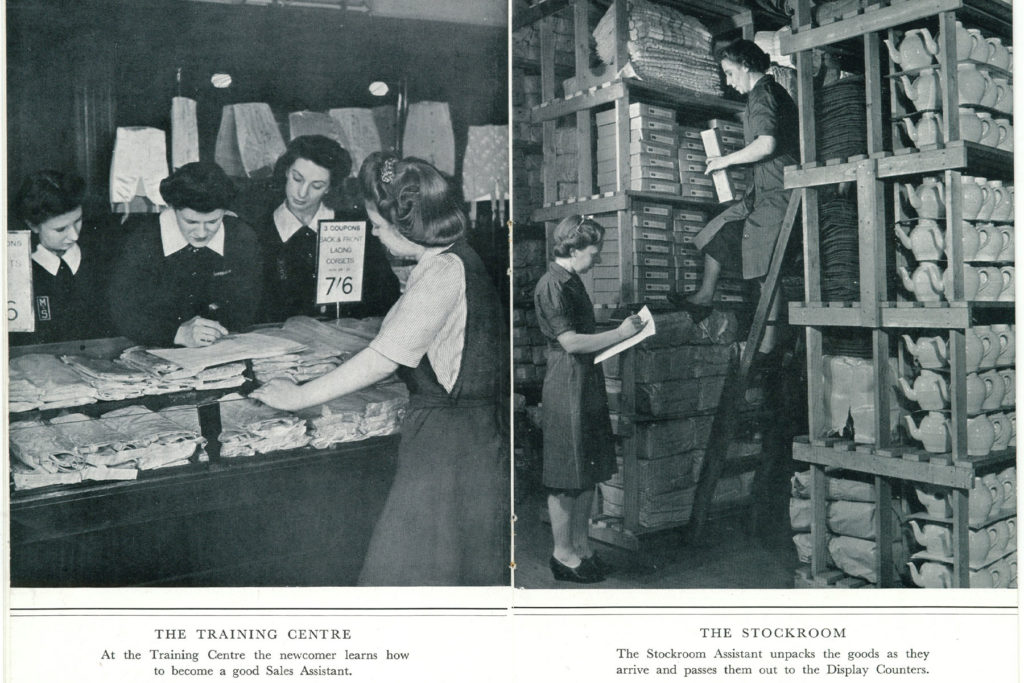

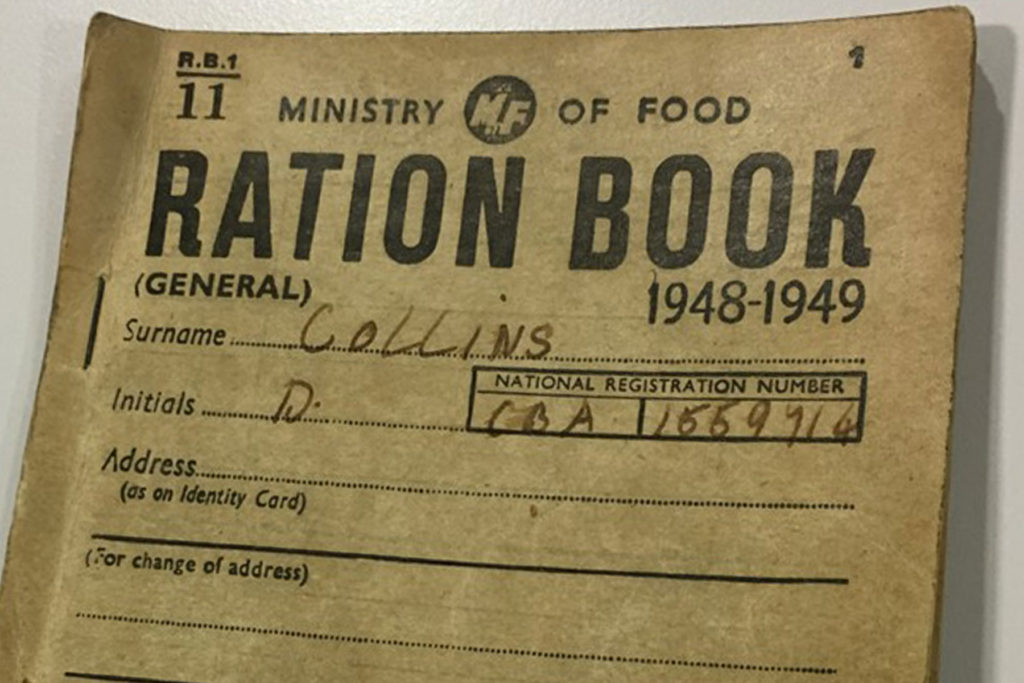

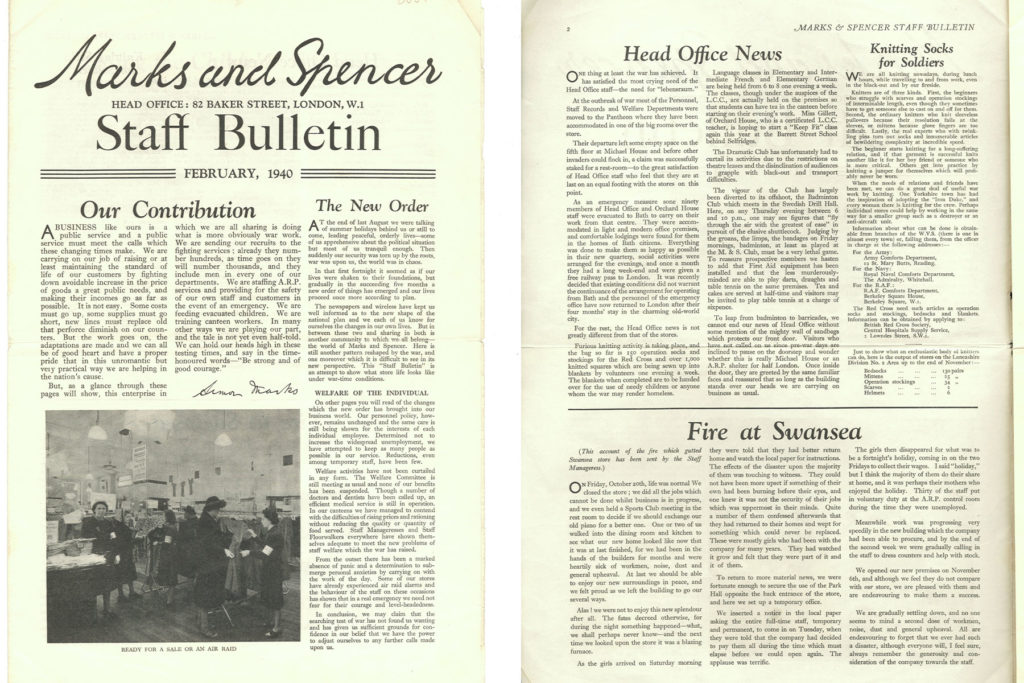

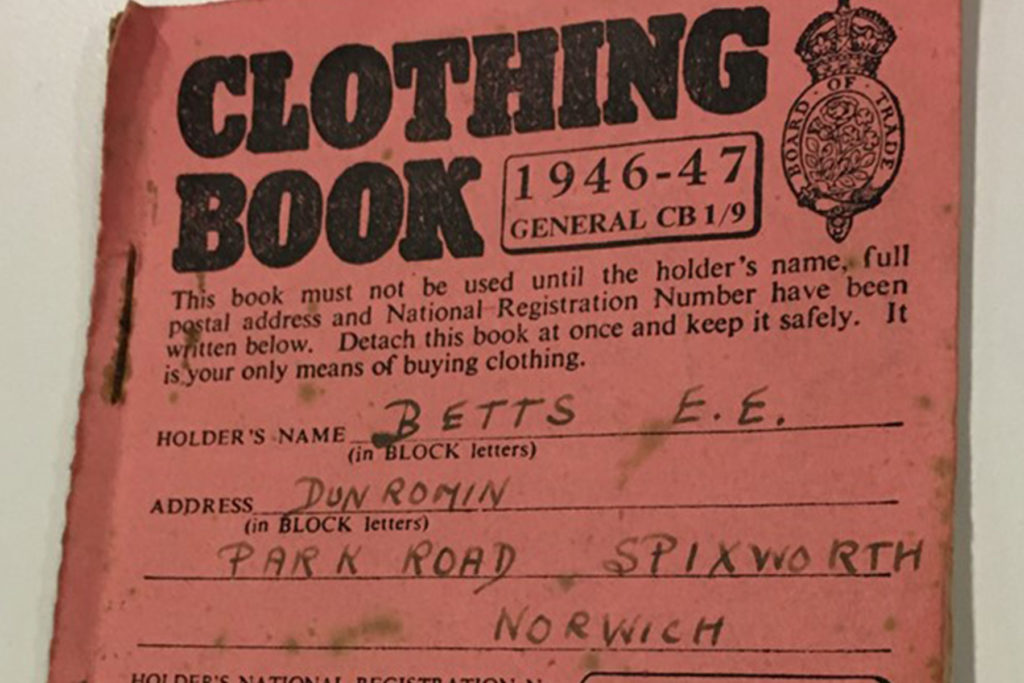

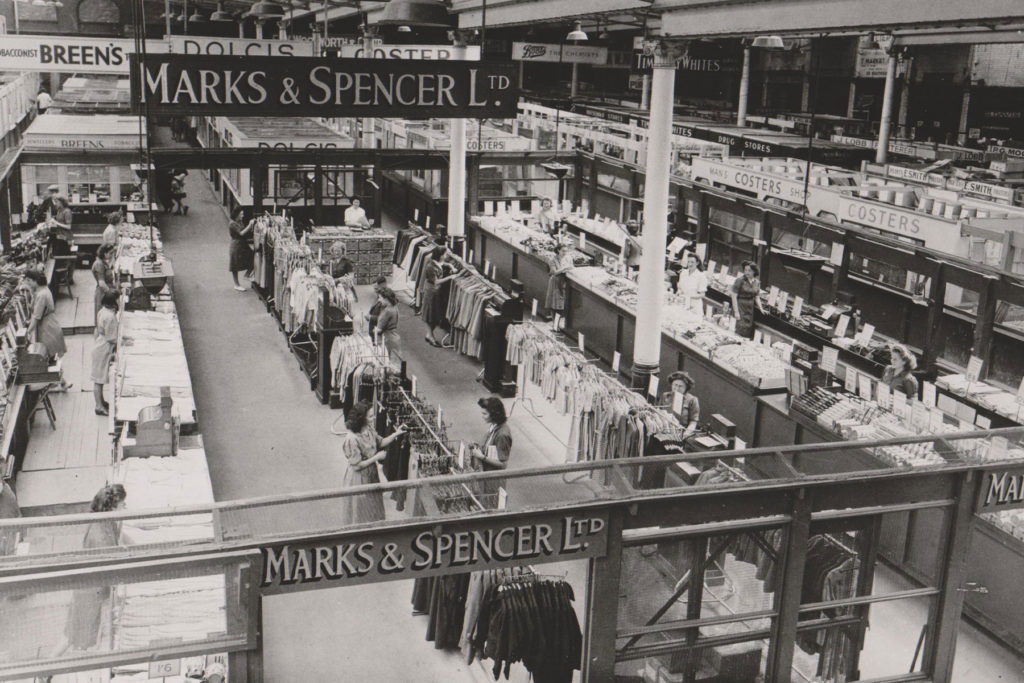

This exhibition explores the challenges faced by M&S during the Second World War, including the impact on employees, stores, fashion and food.

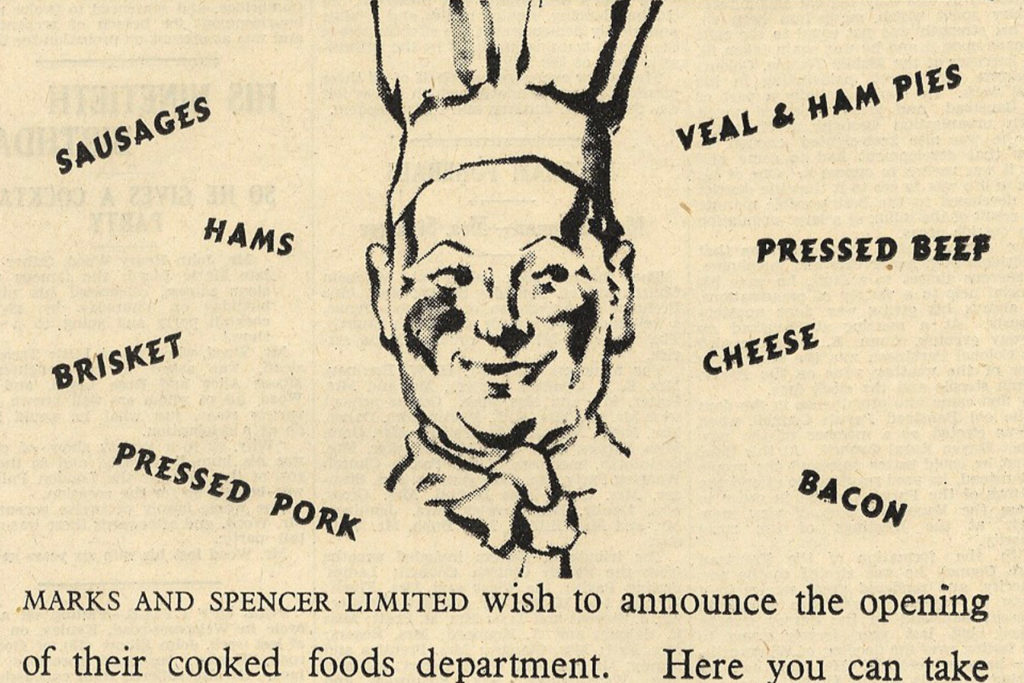

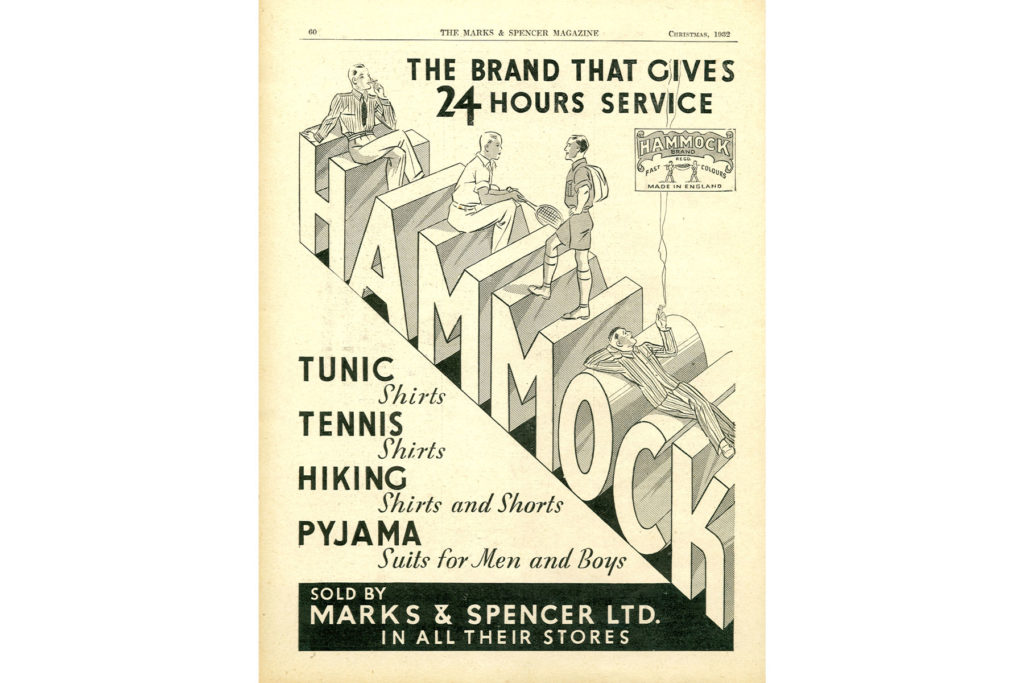

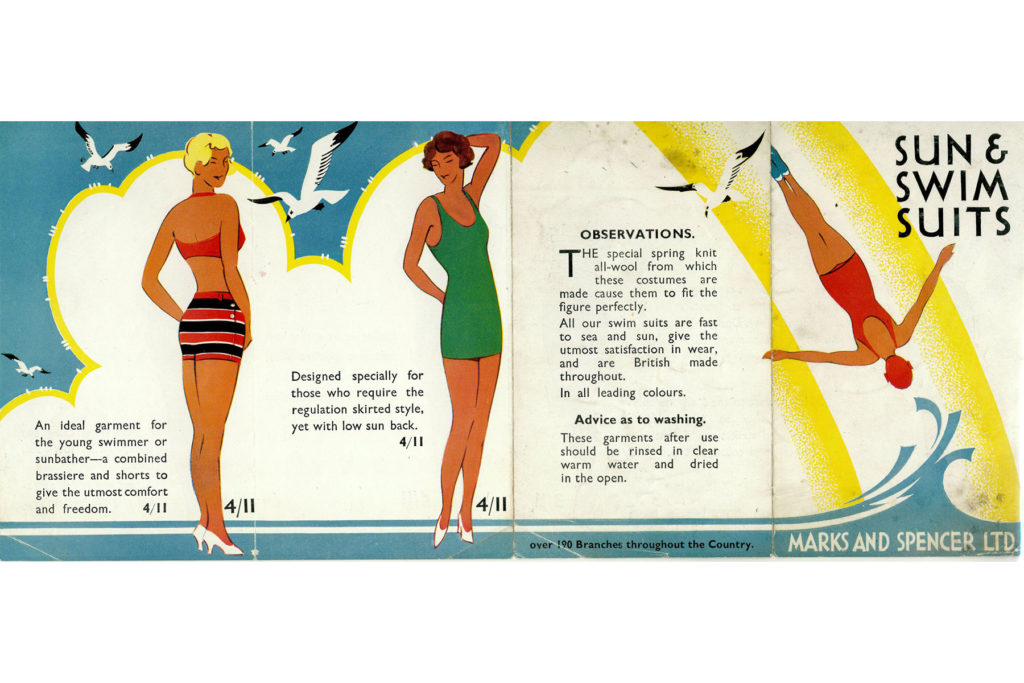

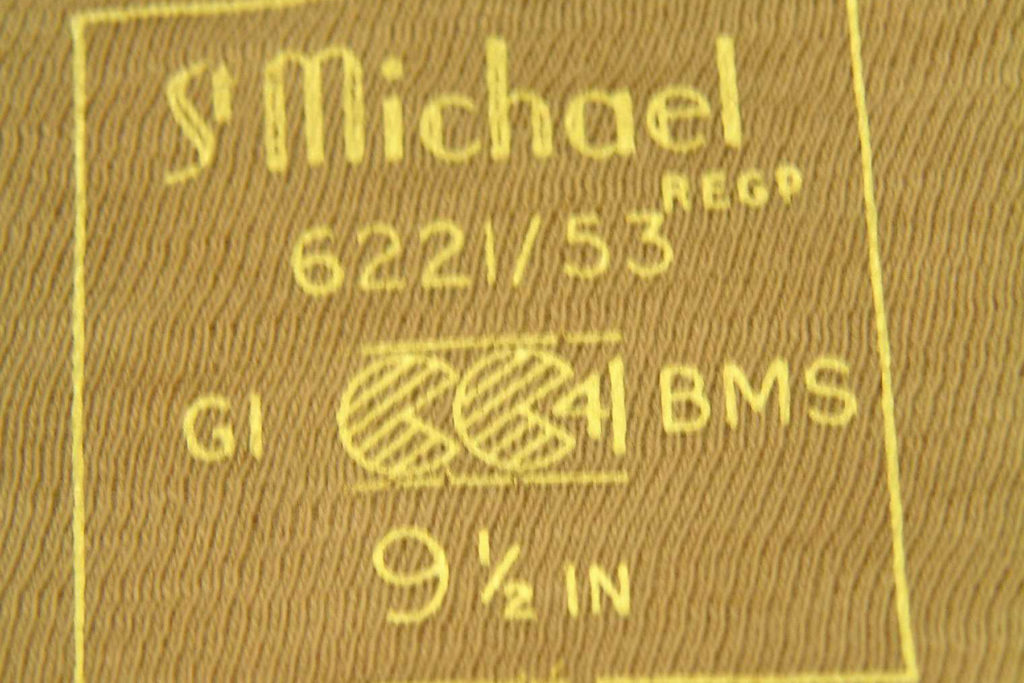

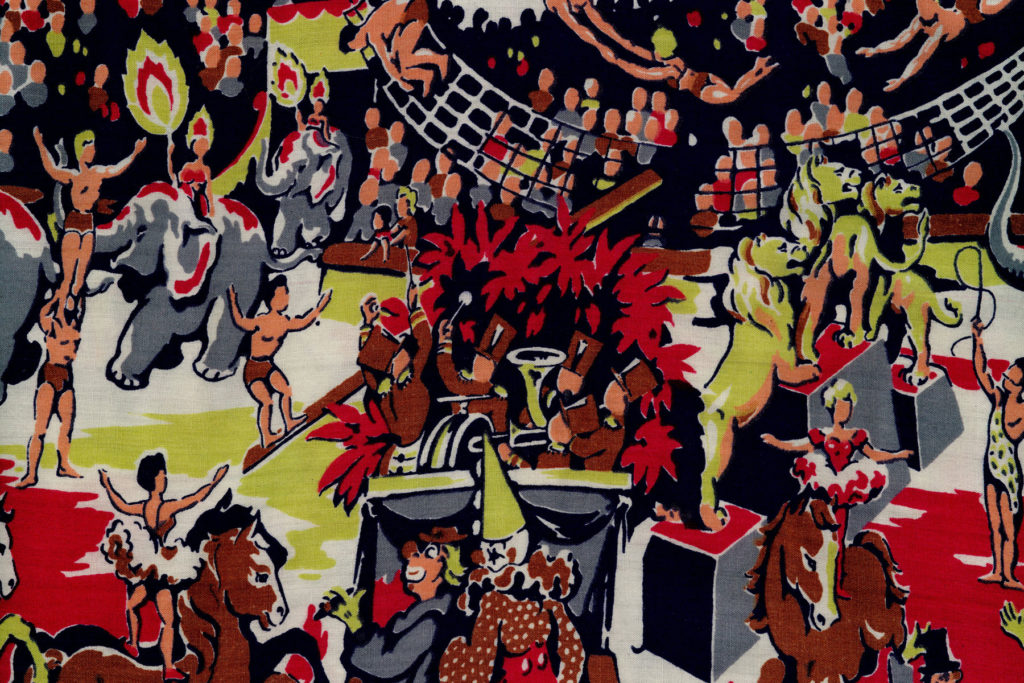

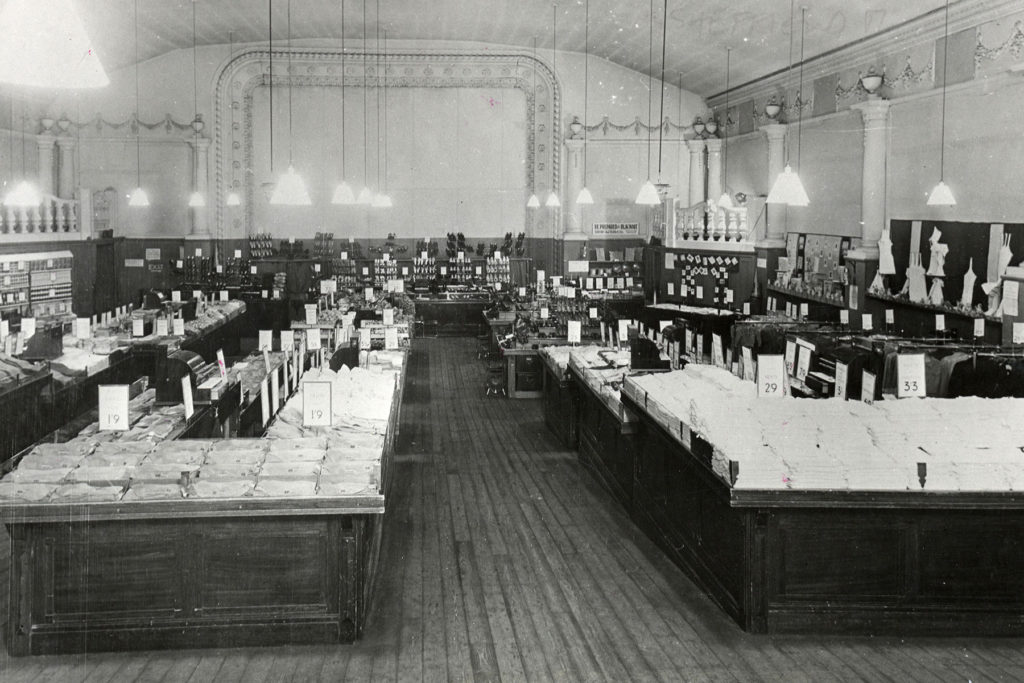

The 1930s was a period of huge expansion for M&S. Our product range had grown throughout the 1920s and we started selling clothing in 1926.

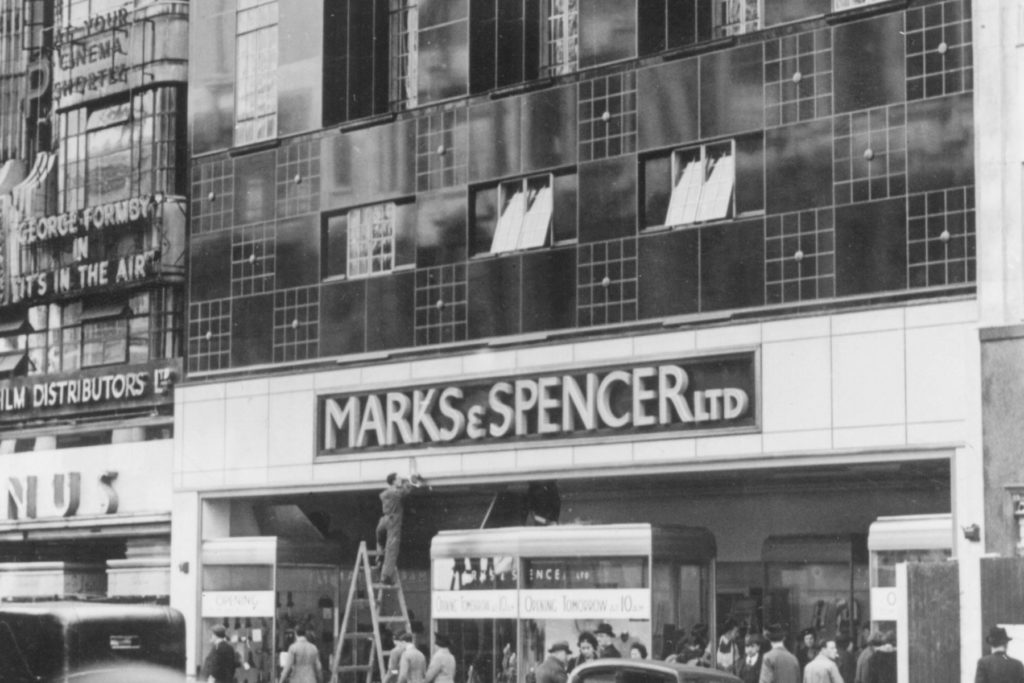

This meant that we needed larger stores. Between 1926 and 1939 165 new stores were built and old stores extended. At the start of the war there were 234 M&S stores.